2 Portland Place

A potted history.

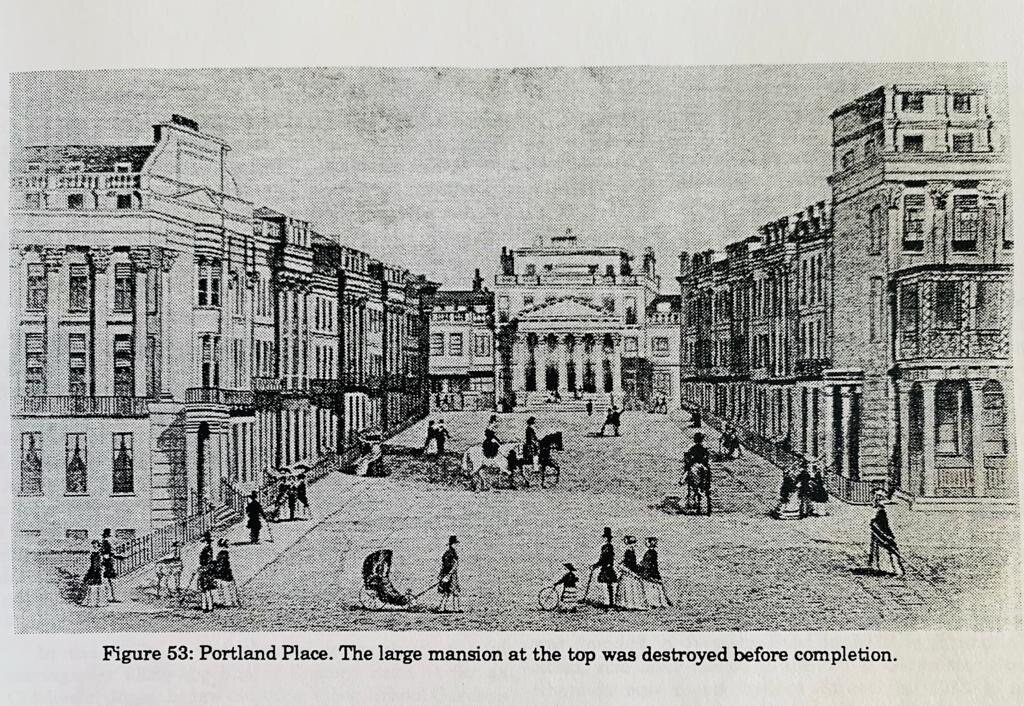

The development of Portland Place, just off the Kemp Town seafront commenced around 1824 on land that was owned by Major Villeroy Russell.

Major Russell commissioned the prolific local architect, Charles Augustin Busby.

Busby designed the streets and houses of what was the first development between Royal Crescent and Kemp Town. The design allowed a broad vista from the Major's Portland House which was situated at the top. but the project was not without incident. On the 12th of September 1825, the classical mansion that was to be home to the Major caught fire and was totally destroyed before it was even completed. As it was not insured, Major Russell had to bear the estimated £12,000.00 loss himself.

The site was re-designed to replace the main house with three buildings which would become known as West House, Portland House and Portland Lodge, although they stood on the northern side of St George's Road.

All three properties were later merged into one, West House, which was acquired at the end of the First World War by the St Dunstan's Institute and later renamed Pearson House. Having become a listed building by the 1970s, it was rebuilt in 1971 with the facade preserved.

The two elegant terraces of Portland Place are symmetrical compositions of the neo-classical design typical of the Regency period. They consist of opposing five-storey terraces where every third house has Corinthian pilasters; some are stucco whilst others have yellow brick inserts and all have balconies with ornate ironwork.

Building work continued in the street almost up until the 1850s so the dates of individual buildings can vary considerably.

The houses were typically built of masonry outer walls and timber construction within. The walls are mainly bungaroosh (or bungarouche – there are many variations in spelling!) within a brick framework. This is a local construction method where lime mortar was poured into shuttering and flints from the Downs or the beaches were literally 'bunged' in; quite often anything else to hand was also 'bunged' in including old bricks, pieces of wood and lumps of chalk. This process was continued a few layers at a time to allow setting to take place before too much weight was loaded.

The houses were typically built of masonry outer walls and timber construction within. The walls are mainly bungaroosh (or bungarouche – there are many variations in spelling!) within a brick framework. This is a local construction method where lime mortar was poured into shuttering and flints from the Downs or the beaches were literally 'bunged' in; quite often anything else to hand was also 'bunged' in including old bricks, pieces of wood and lumps of chalk. This process was continued a few layers at a time to allow setting to take place before too much weight was loaded.

This construction method meant that the walls would constantly settle, dictating that a render with the same properties had to be used to ensure the bond between flint, mortar and render not be lost. Lime render was used and has continued to be used throughout the life of these buildings.

Timbers were purchased 18 months in advance and laid in a lime pit to dry out, helping to retain their strength and prevent decay. The joists in Portland Place are typically 33 feet in length, something unheard of today.

A History of Brighton + Portland Place in images

In recent years the Regency Society nominated 2 Portland Place as one of the most at risk buildings in Brighton and Hove and until the summer of 2015, the faded grandeur of it's façade gave absolutely the wrong impression as to its recent history.

The building was neither forgotten nor unloved; it's previous owner, who was actually born in the house, felt so strongly about it that he chose to take on the labour of love that restoring the building would entail.

He began the meticulous stripping back of the property in 2004: eleven skips were filled – eight for the old plaster alone – to take the building back to its bare bones in preparation for the work ahead.

Windows were restored, including the stunning two-storey high arched window at the rear of the house that spans the first and second floors. The lower section is made up of twelve panes of glass, the arched top section consists of thirteen and afficionados of the period have commented that they have never seen so tall a window in a property of this size.

The naked building also revealed all kinds of interesting facts: a large wooden framework connected to the chimney breast on the first floor is testament to an error on the part of the original builders who, having built the chimney in the wrong position, had to build the frame to make the fireplace look symmetrical.

Sadly that is the point at which the project stalled, when the sheer scale of the task became overwhelming and the house was put up for sale.

It is rare to find a Regency townhouse that has not been converted into flats, rarer still that the subsequent buyer has decided to continue the renovation in a manner and style befitting such a building of note.

Enter Ian Lawson of Indigo Property Group whose dream it was to do just that; to return this elegant building to it's former glory.

Images and information courtesy of

Society of Brighton Print Collectors | The history of Brighton & Hove in lots of bits | History Women Brighton | Francis Frith Photos | Kemptown Estate Histories | Culture 24 | My Brighton and Hove | Kemptown.com | Brighton Museums